Amund Dietzel

Amund Dietzel | |

|---|---|

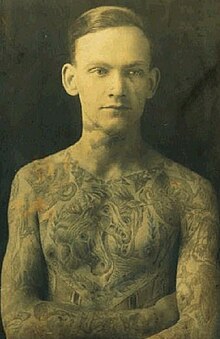

Dietzel in 1914 | |

| Born | 28 February 1891 |

| Died | 9 February 1974 (aged 82) Oconomowoc, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Occupation | Tattoo artist |

Amund Dietzel (28 February 1891 – 9 February 1974) was an early American tattoo artist who tattooed tens of thousands of people in Milwaukee between 1913 and 1967. He developed a substantial amount of flash art, influenced many other tattoo artists, and helped to define the American traditional tattoo style. He was known as the "Master of Milwaukee" and "Master in Milwaukee".

He learned to tattoo as a young Norwegian sailor, but after a shipwreck in Canada, he decided to immigrate to the United States. He became a traveling performer as a tattooed man, then settled in Milwaukee as a professional tattoo artist.

Early life

[edit]Dietzel was born on 28 February 1891, in Kristiania, Norway.[1] After his father died, Dietzel joined the Norwegian merchant fleet at the age of 14.[2] Scandinavia had a maritime tattooing tradition,[3] and Dietzel soon received his first tattoo.[4][5] While working on a ship that transported timber between Canada and England, he began to tattoo his shipmates using a needle tool that he made.[2] In July 1907, when Dietzel was 16, his ship wrecked near Quebec, and he decided to work in the lumber yards there rather than return to sea.[2]

Career

[edit]Art school and traveling carnivals

[edit]After working in Quebec for two months, Dietzel hopped a train and moved to New Haven, Connecticut.[2][6] In New Haven, he took some art classes at Yale University while working as a tattoo artist at night.[7] He wanted to be a fine-art painter, but he could not afford to continue studying art at Yale, so he became a full-time tattoo artist instead.[7] Around this time, he started using an electric tattoo machine.[6] He made friends with William Grimshaw, an English immigrant who was also a developing tattoo artist.[1][2] Grimshaw gave Dietzel a suit of tattoos, and Dietzel may have tattooed Grimshaw in return.[8] Together, they performed in traveling carnivals and circus sideshows as tattooed men, where they sold photos of themselves and tattooed customers in between shows.[1][5] Dietzel and Grimshaw used tattoo ink made with carbon black, "China red" (vermilion), "Casali's green" (viridian), Prussian blue, and a yellow pigment that may have been arylide yellow.[9]

Milwaukee

[edit]

In 1913, Dietzel arrived in Milwaukee and found that nobody was tattooing there.[10] He decided to stay and set up shop in an arcade.[6] His business occupied various downtown locations over the years, and he sometimes shared space with a sign painter.[10] Dietzel was known to wear formal clothes at work, such as a vest and tie with rolled-up shirtsleeves,[11] and even sleeve garters.[12] Many of his customers were soldiers and sailors who served in World War I and World War II.[1] By 1949, business had declined, so he also worked as a sign painter.[7]

In the early 1950s, most of his customers were sailors on leave from Naval Station Great Lakes.[13] He said that the Navy was discouraging tattoos of naked women, so he was often asked to add clothes to existing tattoos.[13] His designs at that time included a full-rigged sailing ship labeled "Homeward Bound", a woman wearing a sailor cap, dragons, peacocks, mermaids, and skull and crossbones.[13] In the mid-1950s, he said that he had tattooed more than 20,000 customers.[8]

He became known as the region's leading tattoo artist.[2] Many tattoo artists came to Milwaukee to get tattooed by Dietzel and to learn from his techniques, including Samuel Steward.[14] He developed a large quantity of flash art — at one point, he said that he had developed more than 5,000 designs[7] — and contributed to the development of the American traditional tattoo style.[15][16] He was called the "Master in Milwaukee", "Master of Milwaukee", and "Rembrandt of the rind".[4][10][17]

Dietzel also painted landscapes and birds, and he took classes at Layton School of Art in Milwaukee.[10]

End of career

[edit]In 1964, at age 73, Dietzel sold his shop to his friend and collaborator Gib "Tatts" Thomas.[2][18] In February 1967, Thomas said that he and Dietzel had "covered more people for exhibition than any two people in the United States", but that few people wanted to become tattooed sideshow performers anymore; most of their recent customers were sailors or businessmen.[19] Dietzel and Thomas continued to tattoo together until the Milwaukee city council banned tattooing on 1 July 1967.[1]

Personal life and death

[edit]Dietzel was married four times.[11] In the 1940 census, he is listed as living in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, with his wife and daughter.[20]

Dietzel died of leukemia on 9 February 1974.[2] The probate section of The Waukesha Freeman newspaper stated that he was from Oconomowoc, Wisconsin, and had left $28,725.02 (equivalent to $177,467 in 2023) to his heirs.[21]

Legacy

[edit]Samuel Steward, who had learned from Dietzel and kept some of Dietzel's flash in his shop, trained Don Ed Hardy.[12] Hardy went on to revive and promote the American traditional tattoo style that Dietzel had worked in.[12]

Jon Reiter, a tattoo artist who grew up in Milwaukee, heard about Dietzel but could not find much information about him.[11] Reiter started collecting flash art by Dietzel and got in contact with Dietzel's grandsons, who shared boxes of memorabilia and photos with him.[11] He wrote two books about Dietzel and worked with the Milwaukee Art Museum to hold an exhibit of Dietzel's art in 2013.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Tattoo: Flash Art of Amund Dietzel". Milwaukee Art Museum. 2013. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Biondich, Sarah (20 October 2010). "Amund Dietzel: Milwaukee's Tattooing Legend". Shepherd Express. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Sinclair, A. T. (1908). "Tattooing - Oriental and Gypsy". American Anthropologist. 10 (3): 367. doi:10.1525/aa.1908.10.3.02a00010. ISSN 0002-7294. JSTOR 659857.

The Scandinavian (Sweden, Norway, and Denmark) deep-water sailors are certainly ninety percent of them tattooed. It is the tradition among them that the custom is very ancient.

- ^ a b "Tattoo: Identity Through Ink". American Swedish Historical Museum. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b Crimmins, Peter (6 February 2022). "How Scandinavian immigrants to America developed modern tattooing". WHYY. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ a b c Eldridge, C.W. (2016). "Amund Dietzel". Tattoo Archive. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d Adam, Carl H. (19 October 1949). "Master Tattoo Artist Thinks Fad May Be on Its Way Out". Green Bay Press-Gazette. Green Bay, Wisconsin. p. 8. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b Strini, Tom (20 July 2013). "Tattoo art history at the Milwaukee Art Museum". Urban Milwaukee. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Miranda, Michelle D. (10 September 2015). Forensic Analysis of Tattoos and Tattoo Inks. CRC Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-4987-3643-5.

- ^ a b c d Tanzilo, Bobby (23 July 2013). "Celebrating Milwaukee's own Rembrandt of the rind". OnMilwaukee. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Needle Points". Milwaukee Magazine. 2 July 2013. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b c Lodder, Matt (2015). "The New Old Style: Tradition, Archetype and Rhetoric in Contemporary Western Tattooing". Revival: Memories, Identities, Utopias. London: Courtauld Books Online. pp. 104, 110. ISBN 978-1-907485-04-6. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ a b c "Tattooing Is Not Popular: Once Good Business Has Lost Its Vogue With Tars". The Daily Chronicle. De Kalb, Illinois. 22 April 1953. p. 6. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Weisberg, Louis (7 September 2018). "Tattoos — from rebellion to conformity". Wisconsin Gazette. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Gillogly, Kate (8 October 2013). "Flash Art of Amund Dietzel". Tattoo Historian. Archived from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Schubertsays, Dean (31 July 2013). "Telling Tattoos: Harold Wright Remembers Amund Dietzel". Milwaukee Art Museum Blog. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ "Museum Opens First-Ever Tattoo Art Exhibition". Milwaukee Art Museum. 25 June 2013. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Eldridge, C.W. (2017). "Gibs "Tatts" Thomas". Tattoo Archive. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Hartnett, Ken (13 February 1967). "Trend Toward Hideous in Tattooing Profession". Manitowoc Herald Times. Manitowoc, Wisconsin. p. 23. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Amund Dietzel in the 1940 Census". Archives. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Probate". Waukesha Freeman. 2 November 1974. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- These Old Blue Arms: The Life and Work of Amund Dietzel by Jon Reiter. Solid State Publishing, 2010, ISBN 978-0-578-05967-9.

- These Old Blue Arms: The Life and Work of Amund Dietzel, Volume 2 by Jon Reiter. Solid State Publishing, 2011, ISBN 0-578-05967-3.

- Bad Boys and Tough Tattoos by Samuel M. Steward. Routledge, 1990, ISBN 0-918393-76-0.